Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

Hi John,

I don’t have a photo of my cheater cord but it’s basically an extension cord with the female end chopped off, the wires split apart, and then terminals crimped on the ends for easy connecting. Ain’t nuttin to it!

It go into timer charts in detail in the Advanced Troubleshooting course. But here’s a little video I made for a tech over at Appliantology explaining how to use the timer chart and schematic together to figure out how the circuit should work in a Whirlpool top load washer:

Hi Atta,

We can talk about this from a theoretical and troubleshooting point of view. But I won’t have any product specific information for you that may be relevant to this case.

A couple questions:

– is the condenser fan running and the condenser fan clean?

– what are the specifications for the normal high and low side operating pressures?

Hi George,

We’re really measuring the voltage *across* the door switch. With the switch open, I would measure the supply voltage across the switch contacts. The switch could be open due to no being actuated or from an internal failure inside the switch (arced contacts, mechanical actuator failure, etc.).

“Not fine” in this context is a colloquial way of saying “the switch no longer conforms to manufacturer specifications.”

If the door switch is not fine, there would be an open circuit.

Most commonly, yes. Sometimes, however, the contacts inside the switch can become damaged due to arcing to the point were they do longer act like a wire when closed and their resistance may increase due to heat as current travels through them. This will show up on your meter as some amount of voltage drop across the switch contacts. The voltage drop across the contacts of a closed switch that is operating within specifications should be 0 (or very close to it– a few millivolts may show up on better meters). In switches that fail this way, you’ll typically see some significant voltage drop across the contacts, usually more than 10 volts. In this case, the defective switch is not creating an open circuit but it has now become an undesirable load in series with the intended load and is “robbing” voltage from the intended load by dropping some of the supply voltage across it.

Make sense?

Hi George,

Since the circuit is completed through each of the light bulbs, removing one of the bulbs from the circuit would have the same effect as one of them burning out (ie., the filament failing open).

Hi Leroy,

Most of the black gookus in the oil is burnt oil and some of it is metal powder produced by the moving parts (piston, bearings, etc.) of the compressor during operation. Depending on the specific failure, there may be some burnt varnish from the motor winding insulation.

Air, being mostly nitrogen, is a non-condensible in a refrigeration system. This means is just stays in there like a bubble and never changes state from vapor to liquid– it just remains a gas, raises head pressure and reduces the refrigeration capacity of the system.

Moisture (and the component of air that is oxygen) participates in chemical reactions in the system producing acids and contributes the degeneration of compressor and motor. The moisture can also form ice plugs at the point where the capillary tube (high pressure) enters the evaporator (low pressure). Evan a small amount of moisture can cause this problem. For this reason, all refrigeration systems have a filter drier to remove particles, protecting the compressor mechanical components from damage, and absorb moisture.

Hi Mike,

Can you be more specific, please? What specific problems are having with the questions?

Keep the faith, Sal, and look at these mistakes as part of your on-the-job training. You should really be thankful for these learning opportunities. In the scheme of things, it only costs you a few bucks for parts and some time. The only real losses in these situations can be a customer– but as long as you make it right with them, you’ll turn lemons into lemonade because they’ll see that you’re a man of integrity who follows through and does what he says and your reputation will grow by word-of-mouth.

Since you started a topic on this at Appliantology and already got a couple of replies (including one from me), let’s continue the discussion there so the topic has develops and gets closure. These are perfectly reasonable followup questions to ask in your topic there.

Scott

Hi Sal,

Let’s think through this:

All PTC thermistors are designed to react to an increase in temperature by very rapidly increasing their resistance as temperature increases. This property makes them useful for all kinds of applications such as heaters in wax motors as well as start “relays” (though they aren’t relays at all) for split phase compressors.

Recall from the Refrigerators course that the whole purpose of the start device (more general term for when the PTC pill is used) is to take the start winding out of parallel with the main winding when motor after the motor starts and is just running on the main winding. To do this, the current through the PTC heats up the PTC which causes its resistance to increase rapidly to a high level, effectively open to current flow. So at the instant of start, before current starts flowing, the resistance of the PTC is very low, on the order of several ohms. After current flows through it and the compressor motor is running, the PTC heats up and its resistance increases to Mega-ohms. So the test for the PTC is to simply measure its resistance at room temperature.

This webinar recording goes into detail on PTC thermistors as well as several other type of temperature reaction and measurement technologies used in modern appliances:

The other type of start device is you referred to is the Time Start Device – TSD. It does the same function: closed at start and then open when the compressor motor is running. Whereas PTC devices most commonly fail open, the typical failure mode on TSD devices is to fail closed, meaning they never open and take the start winding out of the circuit. So the compressor runs for about 10 seconds or so, drawing excessive current because the start winding is still in parallel with the main winding, causing the compressor’s overload device (the klixon) to open and kill power to the compressor motor. The only way to test this is operationally: knowing that a TSD dev ice is being used, run the compressor while measuring it’s amps. If the amps are excessive (something well above 1 amp) for several seconds and then the compressor overload opens, then the TSD has failed closed. The klixon will measure open.

This video explains the operation of the PTC and TSD devices:

Hi David,

I want to give some general procedural tips when researching any diagnostic issue with an appliance you’re working on.

Step 1: GET AN ACCURATE AND COMPLETE MODEL NUMBER! Case in point here is that the model number you gave is incorrect. As a professional tech, this is Job One. Why is this so important? Because of Step 2…

Step 2: Look up manufacturer technical literature. You won’t find this with an incorrect model number.

Sam will post some other pointers for you.

Scott

What if the signal wants the motor to stop. You still have 12 volts at the motor but it is not running how do you know that the motor is bad or is it just the board telling it to stop.

Great question, Sal! This situation does happen with computer-controlled appliances where the microprocessor is executing a program and making “intelligent” decisions about which load to activate and under what circumstances.

For example, some BLDC fan motor configurations have an RPM feedback line that tells the MICOM how fan the fan is turning. The MICOM algorithm may go something like this:

– compartment thermistor reports warm temperature

– turn on evaporator fan motor

– verify fan motor speed from RPM line

– if RPM = 0 for 15 seconds, kill power to fan motor and retry in 15 minutes; repeat this attempt three times

– if still no RPM feedback after the third attempt, kill power to fan motor and report an error.Usually, you’ll only see operating voltage at an inop fan motor in models without the RPM feedback line because the MICOM has no other way to know whether or not the fan motor is actually running without it.

I realize you can put the board in diagnostic mode and see if it spins on but is there another way using a meter.

This is exactly the way to test this. On Samsungs, for example, they call this “Forced Mode” where you bypass the program and instruct the MICOM to make the fans run regardless of any previous error states. While in forced mode, you can check the operating voltage and PWM speed signal to the fan all from the MICOM board. You would do this to verify that the MICOM is doing what it’s supposed to do. If you have these signals and the fan still doesn’t run, then you know the problem is either a bad motor or bad wire harness.

If you can identify the various lines to a board– VCC, DC GND, PWM, and RPM– you can also “hotwire” the fan motor using a 9V battery. I show this on a GE fridge below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZOYlrjd2rnQ

Make sense?

Dave,

1) Yes

2) Yes

🙂

My question is what do they mean by high side and low side of refrigeration cycle. Are they talking pressures?

Yes, exactly!

So the low side is the intake to the compressor all the way back to where the LIQUID refrigerant enters the evaporator, before it boils (“expands”) into a gas. Physically, this is the exact point where the capillary tube enters the evaporator coil. The pressures all throughout this side of the sealed system are the same.

The high side is the discharge of the compressor all the way to the point of LIQUID refrigerant boiling (expansion) in the evaporator. The pressures all throughout this side of the sealed system are the same.

The point of refrigerant boiling (or phase change or expansion, all the same thing) is where the pressure transition from low to high occurs.

Discharge confuses me.

“Discharge” refers to the discharge from the vapor pump, the compressor. The compressor is the mechanical component that makes this essential pressure differential possible. All hail the compressor!

Just a follow up note on Neutral:

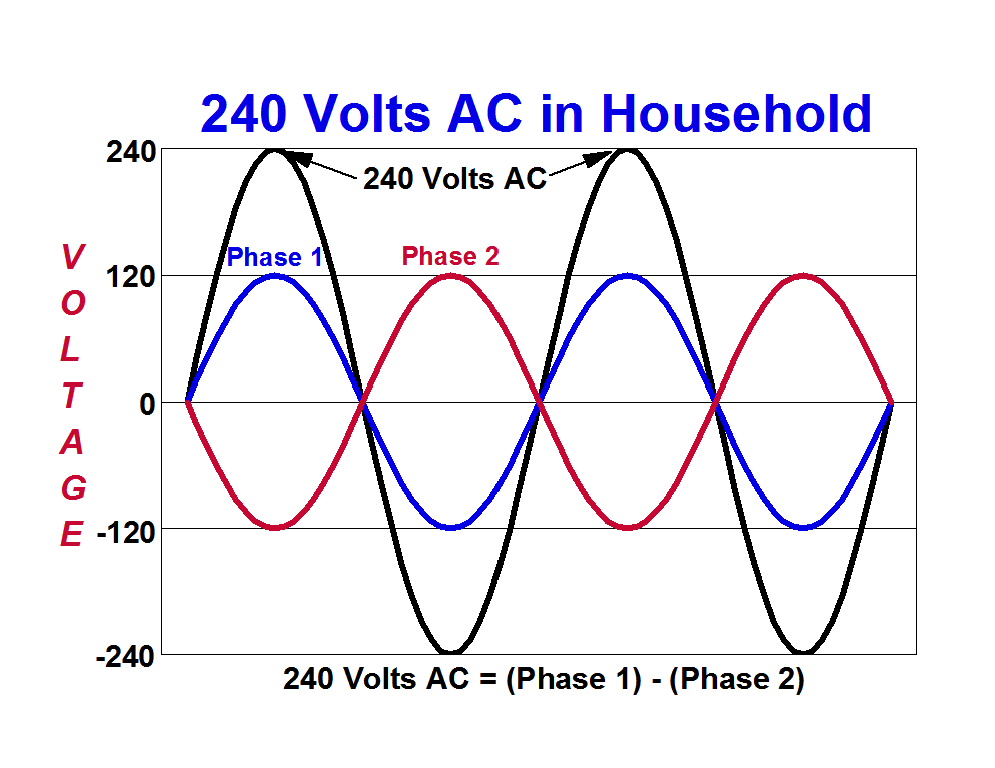

We’re dealing with split phase power supplies. That means getting both 240 and 120 VAC from a single phase. In other words, “splitting” a single phase into two phases. This is easily done with transformers using a center tap because of the way transformers work.

Neutral is there to provide a return path to the power supply for 120 VAC circuits. The return path in this case is the center tap on the transformer secondary winding. This IS the definition of the Neutral wire!

For 240 VAC circuits, L1 and L2– each end of the transformer secondary– take turns acting as returns for other as time goes on. At one half cycle, L1 is more positive than L2 and so electrons are attracted to it as the return. And that’s where they go. The next half cycle, L2 is more positive than L1, so the electrons happily change directions and use L2 as their return to the power supply.

And so the great electronic dance continues for all eternity… or until North Korea detonates a high altitude nuke that generates a huge EMP spike and takes down the entire power grid. But that’s another story.

BUT L1 and L2 are synchronized together instead of 180 degrees off? I guess it couldn’t be 240 since there wouldn’t be a net difference and it would be the same as 120VAC on both sides or EEP?

You are correct! Two AC voltages that are the same amplitude and in phase with each other will never have a voltage difference between them at any time. The net voltage difference will always be zero. The voltages must be out of phase by some amount (degrees) for there to be a voltage difference.

Look at this image below:

They are the same amplitude and always change at exactly the same time (ie, are in phase with each other). This image is a depiction of a fictional L1 and L2 in relation to each other– the real L1 and L2 are 180 degrees OUT of phase with each other (mirror images).

Remember that voltage is always measured with respect to some other point or reference. We call this the voltage DIFFERENCE between two points. DIFFERENCE has a technical, mathematical meaning– it means SUBTRACTING two things.

Now look at the voltage difference at any time between those two sine wave. Three example slices are indicated with blue, pink, and red dots. The net voltage DIFFERENCE at any point between those two sine waves is always exactly zero.

So, in your example, if L1 and L2 are synchronized (ie, in phase) with each other, then there would be no voltage difference so no potential for current to flow and hence no shock hazard.

See if this video helps:

Well, we were there waiting for you until quarter past 10. Sorry you couldn’t make it. Hope everything’s alright.

This will make a good topic for the next Office Hours. I’ll announce it in the newsletter.

-

AuthorPosts